Apologies for the ethno-blog hiatus, since May I have been in el monte (i.e. backcountry, a term synonymously used with la selva, or jungle), several hours up the Madre de Dios River. I am now based in the capital city of Puerto Maldonado for a more prolonged period and will update the ethno-blog regularly. There are many exciting stories, videos, photos, and more to share in forthcoming posts! Over the past few months I have been conducting participant observation and semi-structured interviews with a variety of local people, including permanent and temporary staff at a conservation concession/biological station, eco-tour guides and operations staff (e.g. motoristas, logistics, etc.), local assistants of science investigators, and other locals whose livelihoods are intertwined with the conservation economy in Madre de Dios.

TRAVERSING THE LANDSCAPE

Since 2008 I have been traveling upriver to learn about the role biodiversity conservation and natural resource extraction play in local livelihoods, but I am also keenly interested in how these economies define and transform space. It was serendipitous that my longitudinal research in Madre de Dios began as the latest gold boom commenced following the global economic recession (see Asner et al. 2013). To help me understand the effects of transnational development and natural resource extraction, I have been photographing these trips for the past six years and using images as props in photo elicitation interviews and analyzing photographs using methods from cultural geography, such as landscape interpretation (see Duncan et al. 2004).

Below are a few selected photos that document the trip from Puerto Maldonado to a biological research station several hours up the Madre de Dios River:

PARTICIPANT OBSERVATION

My last ethno-blog update focused on semi-structured interviews I conducted with merchants of agricultural products during the paro regional (regional workers’ strike) with the objective to better understand from an emic perspective how local livelihoods were affected by the longest paro in recent history of Madre de Dios. Whereas in the last entry I described preliminary results from semi-structured interview data, in this post I will discuss a different ethnographic method—participant observation—and what kinds of insights can be gleaned by this approach.

For readers new to anthropology and the practice of ethnographic inquiry, participant observation is a cornerstone of our disciplinary methodology and involves active engagement with the people under study. As it might be inferred by the wording, participant observation entails participating in social life and simultaneously observing it. Participant observation is a craft that can be used to accomplish a variety of ethnographic undertakings, such as to:

- learn a new language/increase fluency and to gain ‘communicative competence’ (i.e. to learn about the rules of communication within a community; see Briggs 1986, read the intro book chapter HERE)

- hang out and build rapport with research participants

- reinforce neutrality (becoming aware of inherent biases based on one’s own gender, class, religious background, upbringing, etc.)

- reduce reactivity (the phenomenon in which people alter their behaviors when they know they are being studied, see Gary Larson Far Side comic below for a satirical example)

Participant observation can be useful to generate both qualitative and quantitative data; as methodologist Russ Bernard (2011: 257) describes, participant observation “puts you where the action is and lets you collect data… any kind of data you want, narratives or numbers.” Indeed, whether I am engaged in daily labor tasks with a conservation worker and eliciting narratives about risks of trapping jaguars for research (one time a jaguar suddenly awoke while undergoing an immobilization procedure and required manual restraint—the local assistant had to jump on its back) or whether I’m pursuing more quantitative questions and assessing a worker’s wage earnings as he plans his next 8-day cachuelo (temporary work) for ~1500 soles compared to his normal S./1100 monthly salary in conservation, participant observation is a powerful mixed-method for the ethnographic toolkit. See HERE for more on wage differences between gold mining and other livelihoods in Madre de Dios such as agricultural work.

For local people who have one foot in biodiversity conservation and the other in natural resource extraction (whether they work in gold mining or logging or are members of households that depend on diversification strategies that include both conservation and extraction), the use of interviews to immediately hedge into sensitive topics may not be an effective method to elicit reliable, meaningful responses. Surveys or interviews can sometimes impose a set of practices that are alien to some locals and can lead to less reliable responses than if the “interview” is unstructured through the process of participant observation in daily life.

Participant observation has generated meaningful experiences with research participants and has helped me identify and pursue new research questions. For example, hiking with a local investigator’s assistant on trails he made a decade ago and spotting wildlife together led to numerous conversations about his prior involvement in the pelt trade, a short economic boom to which some refer to as “el tiempo de piel” (the time of pelts) that has not been well documented (ethnographically or otherwise) in this region (for more on the history of wildlife hunting in Peru, see HERE).

What does it mean to be both a participant and observer? The participant-observation dichotomy poses some practical issues for conducting ethnographic research. Emerson et al. (1995:18; 2001) describe a contrast between “getting into place” to observe noteworthy events on one hand or to suspend all writerly tasks in order to participate fully and to keep the writing from intruding into relationships established in the field. The former tactic somewhat removes the ethnographer (as observer) from the scene in which he or she is embedded, while the latter approach (ethnographer as participant) requires greater reliance on ‘headnotes,’ small jottings, scratch notes, abbreviated words and phrases, and other fragments of writing that are often later expanded into fuller-fledged field documents.

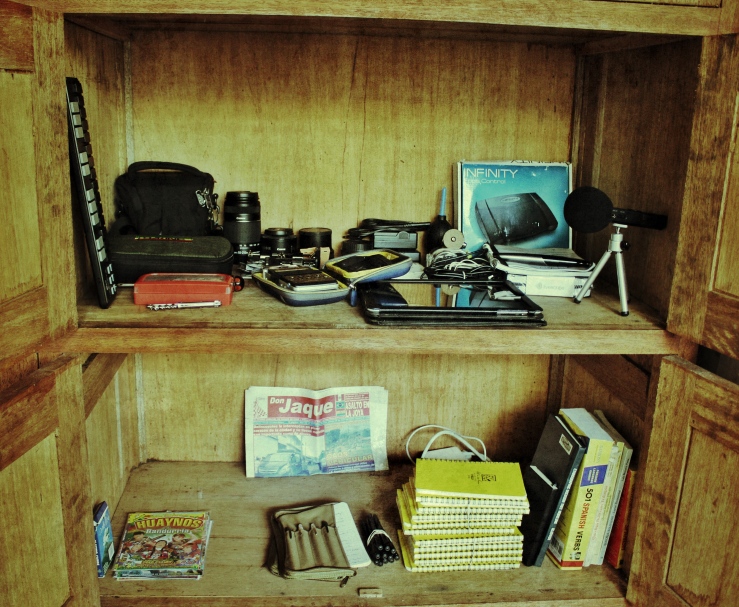

The struggle to determine whether to write or engage (through participation or observation) is a central paradox for the ethnographic fieldworker-writer in general, and certainly a challenge for me during my time in el monte. There were several instances during which all I could do is recite data in my head to commit to memory, as taking notes was not physically possible or socially acceptable. To further complicate matters, my computer broke during the second month of fieldwork, which made note-taking and research more difficult because I typically type up expanded accounts and use qualitative analysis software as an organizational database and archival tool. The ethnographer’s greatest tools when technology fails is pen & paper, astuteness, and memory.

During my time as a participant observer I shadowed my research participants, engaged them in their daily tasks, and observed them interacting in both work and leisure contexts to gain a deeper understanding of what it is like to be a conservation worker in Madre de Dios. Below is brief description of some of the work positions I shadowed and observed:

- Promotores (equivalent to park ranger): Patrol river in concession, check on abandoned station, monitor wildlife, act as guide (taking groups of visitors to mammal clay licks), assisted with anaconda captures

- Motoristas/Tripulantes (boat crew member): Watch the river for potentially dangerous debris and signal the motorista to maneuver boat, help load food, baggage, and other items onto boat, and dock for bathroom breaks (pare técnico) and final arrival to destination

- Asistentes de Investigadores (Investigator assistent: Drive remote control car into giant armadillo burrows, assist in setting up animal traps, assist in tree climbing to look for raptor nests, etc.

- Macheteros (machete worker, trail-maker): sharpening machetes, create and clean trails, trim miradors/outlooks on the terraces

- Ayudantes de Cocina (kitchen helper): prepare garnishes and refresco (juice), serve food, wash plates, clean kitchen

- Mantamientos (maintenance): retrieve nonfunctional motorcar on muddy trail, transport food from port up to the terraces, repair mesh of buildings, repair rooftops

- Guias (tour guide): pick up tourists from airport, transport tourists to rainforest from city, lead tours, identify flora and fauna

Read more about participant observation in this Sage publication. The next ethno-blog post will discuss some of my findings from conducting participant observation research and informal/semi-structured interviews. Stay tuned, I have some amazing stories to share! For now, I’ll leave you with a sneak preview of a forthcoming entry about an anaconda trapping expedition I made on the Los Amigos River with the promotores:

Love the blog. Keep up the great work!

Thanks Hillary! I’m trying to keep things interesting while being informative! Glad you like it!